Editor’s Note: The First Amendment guarantees of freedom of religion and speech are coming under increased pressure today, as seen in numerous cases in which First Liberty Institute and others defending religious freedom are involved. In this environment, it is crucial that more citizens know the history and significance of the First Amendment. It is indeed a “crowning achievement”—and one worth fighting to keep. First Liberty writer Catherine Frappier examines this history below.

With the rise of religious liberty violations and religious hostility in America today, many Americans can likely imagine a world without the First Amendment–and give thanks that the founding generation had the foresight to implement a constitutional protection for the “free exercise” of religious faith.

As part of America’s highest written law for over two centuries, the First Amendment is synonymous with America’s exceptional regard for religious and political freedom.

However, the original Constitution adopted by the 1787 Constitutional Convention did not include a bill of rights with provisions protecting religious freedom and other liberties. So how did religious freedom come to be protected in America’s most basic governing document?

“RELIGIOUS LIBERTY…IS NOT SUFFICIENTLY SECURED”

While the Constitution originally did not include the First Amendment’s expansive religious liberty protection, it did include a few specific religious liberty provisions in “a spirit and purpose similar to…the free exercise clause,” noted the Honorable Michael McConnell (a law professor who later became a federal appellate judge) in a Harvard Law Review article titled “The Origins and Historical Understanding of Free Exercise of Religion.” An example he listed was Article VI, which banned religious tests for “office[s] or public trust[s] under the United States.”

But the Constitution’s lack of a bill of rights–including its lack of religious liberty protection–caused some concern. For example, in a letter to Thomas Barbour, the Virginia Baptist minister John Leland listed his objections to the Constitution–objections that ended up being forwarded to James Madison. One of these objections was that “Religious Liberty, is not Sufficiently Secured.”

Leland argued that the Constitution’s ban on religious tests wasn’t enough. He wrote:

…if a Majority of Congress with the president favor one System more than another, they may oblige all others to pay to the Support of their System as Much as they please, & if Oppression does not ensue, it will be owing to the Mildness of Administration & not to any Constitutional defense, & if the Manners of People are so far Corrupted, that they cannot live by republican principles, it is Very Dangerous leaving religious Liberty at their Mercy–… (spelling modernized)

In a December 20, 1787, letter to James Madison, Thomas Jefferson stated what he “[did] not like” about the Constitution, arguing that it lacked “a bill of rights providing clearly and without the aid of sophisms” protection for various rights. The first of these mentioned by Jefferson was “freedom of religion.”

In addition, several state ratifying conventions (or minorities at these conventions) proposed amendments to the Constitution. For example, one amendment proposed by the New York Ratifying Convention was the following:

That the People have an equal, natural and unalienable right, freely and peaceably to Exercise their Religion according to the dictates of Conscience, and that no Religious Sect or Society ought to be favoured or established by Law in preference of others.

As scholar James H. Hutson stated in his book Church and State in America: The First Two Centuries, Federalists didn’t believe a bill of rights was needed. But he also noted that Federalists agreed to seek constitutional amendments after the Constitution was adopted in order to make sure that the states ratified the Constitution.

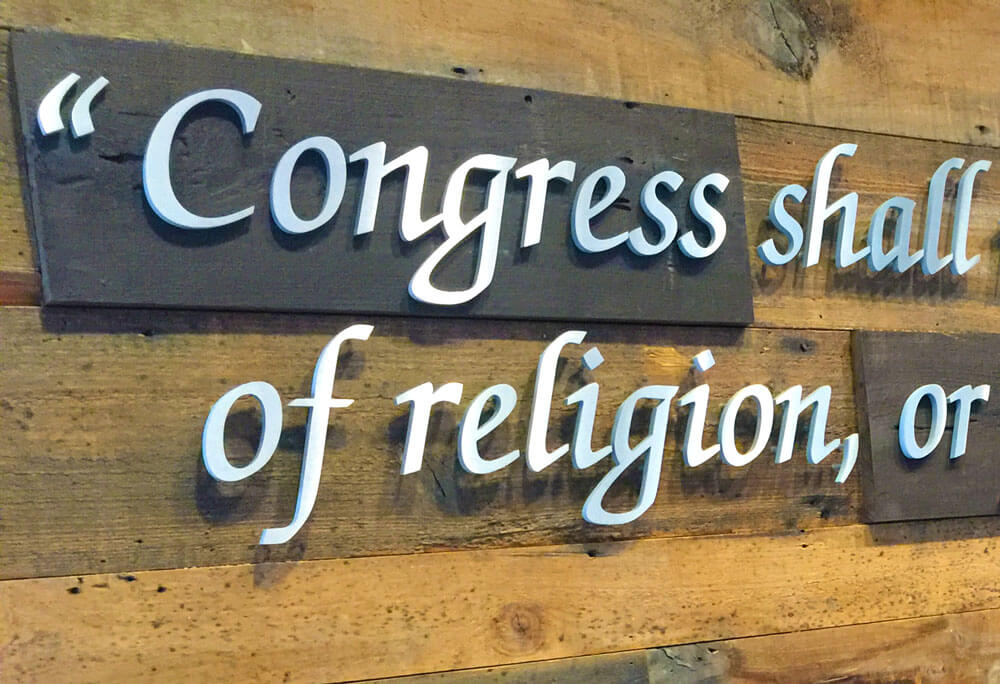

“CONGRESS SHALL MAKE NO LAW…”

So in 1789, James Madison (now a member of the U.S. House of Representatives) introduced several amendments in Congress, including the religious freedom amendment that developed into the religion clauses of the First Amendment.

Madison’s original amendment read as follows:

The civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, nor shall any national religion be established, nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner, or on any pretext infringed….

Madison also proposed two other religious liberty provisions, but these were not adopted by the Senate.

The House of Representatives and the Senate produced different wordings of the amendment. But a conference committee composed of members of both houses of Congress reached agreement on the provision’s language, and the First Amendment (originally the third amendment on the list sent to the states) was ratified on December 15, 1791. It read:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…

Originally, the First Amendment only applied to the federal government, but the Supreme Court later applied the religion clauses of the First Amendment to the states, observed legal scholars the Honorable Arlin Adams (a former federal appellate judge) and Charles J. Emmerich in A Nation Dedicated to Religious Liberty: The Constitutional Heritage of the Religion Clauses.

AMERICA: A MODEL FOR THE REST OF THE WORLD

America can lay claim to many important and special accomplishments, but one of these is the espousal of religious freedom as opposed to the less expansive and inadequate notion of religious “toleration.”

In their work The Sacred Rights of Conscience: Selected Readings on Religious Liberty and Church-State Relations in the American Founding, scholars Daniel L. Dreisbach and Mark David Hall pointed out that from a historical standpoint, the concepts of religious toleration and religious liberty have meant different things.

They noted that toleration has seen freedom of religion as a gift of government that can be taken away, not as a natural right of mankind. In addition, toleration has also often been associated with an established church.

But America chose a different path. As George Washington stated in a 1790 letter to a Hebrew congregation in Rhode Island:

The Citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy: a policy worthy of imitation. …It is now no more that toleration is spoken of, as if it was by the indulgence of one class of people, that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights. For happily the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens… (emphasis added)

Dr. Dreisbach and Dr. Hall called this victory of religious freedom over simple toleration “arguably America’s greatest contribution to, and innovation of, political society.”

PRESERVING RELIGIOUS FREEDOM TODAY

The First Amendment is America’s crowning achievement in the legal protection of religious freedom. In addition, America has instituted several statutory laws that build on the First Amendment and reinforce the concept of religious freedom over toleration.

From the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) to the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) and other federal and state laws, America is a nation that protects its citizens’ “free exercise” of faith.

Today, however, religious freedom is under attack today from hostile governmental and cultural agendas. But America must safeguard its exceptional commitment to religious liberty as a natural, God-given inalienable right of mankind upon which the government must not infringe.

If America does this, its citizens can continue, in George Washington’s words, to “applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy: a policy worthy of imitation.”

News and Commentary is brought to you by First Liberty’s team of writers and legal experts.